A Code of Practice governs independent custody visiting. The document, published by the Home Office and laid before Parliament, outlines the expectations that schemes must meet. It represents high level, but established legislation, culture and practice. It is at the heart of what all schemes do.

Our last Code was published in 2013. It doesn’t sound that long ago, does it? I took a look at some headlines to see what happened that year. Barack Obama was elected for a second term and David Cameron announced that the next Conservative manifesto would include a commitment to an in/out EU referendum. The House of Commons voted to introduce same sex marriage (with weddings taking place the following year) and Prince George was born. Nipper hung up his gramophone as HMV went into administration. It was a world where Trump was a business man and reality TV star, where we were talking about Grexit and where I occasionally still purchased physical CDs.

Policing, too, has changed significantly over this time. The current Code responded to the introduction of Police and Crime Commissioners (PCCs), now embedded in the policing landscape, followed by new mayors. The Scottish Police Authority was established in 2013, reforming custody visiting into a single Scottish scheme. The College of Policing has settled in and published Authorised Professional Practice (APP) for both mental health and detention and custody. The National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC) has published a National Custody Strategy and has a forum to deliver it. Constabularies collaborate more frequently and in greater depth. HMIC and HMIP changed their ‘Expectations for Police Custody’ before HMIC recently became HMICFRS. Moreover, the use of custody cells is reducing as voluntary attendance increases. Custody visiting needs a Code that recognises these changes, enabling visitors to, for example, complete visits across collaborating force areas. It can also be better used to collate and share findings with new national organisations and make positive change.

ICVA’s Business Plan includes an action to review the Code this year and we started to look at it this week. We held a very early research meeting with the IPCC, APCC, UKNPM, NPCC and the College of Policing (well done to the College for a name short enough that it doesn’t require an acronym) – some of the main national bodies in policing. We talked about the value that custody visiting does and could provide and what we may need to do to enable that. A number of initial themes came up.

Questioning the legitimacy of custody visiting

A few people have challenged me on the legitimacy of custody visiting lately. They have done so from different perspectives, but with a general theme that custody visitors are not viewed as community leaders or as representing the public. There are differing views on this area. I know a scheme that has directly reached out and calmed some community fears about custody. I know others that work hard to recruit a representative bunch of volunteers. However, it is also a fair challenge that merits further exploration.

Our schemes do not look like the communities that they represent much of the time. We all bring our own life experiences, assumptions and flexibility to communicate with different people. A diverse group of ICVs will help to ensure that schemes get quality feedback across a range of detainees. I understand the argument that ICVs need to be able to reflect the communities that they represent. No scheme will ever be a precise microcosm of the communities they are recruited from, but we need to understand and, no doubt, improve representation. This is something that we can consider, build on and communicate into the future.

A friend of mine questioned whether ICVs really are independent. He is Liverpool born and bred and is suspicious of the police, having grown up in the wake of Hillsborough. He is exactly the kind of person that I would hope our schemes would reassure. It made me contemplate what we could do with the Code to further develop and explain independence and what we could to do promote the schemes as legitimate public oversight of custody.

The stakeholder meeting further explored these concepts. Our stakeholders value ICV feedback and wanted to ensure that ICVs remain fresh eyed, are respectful to staff, but are very much independent of the police. The emotive issue of tenure was raised and debated – we wondered whether tenure is a natural mechanism for fresh eyes or whether that would throw the baby out with the bathwater? Should we, instead, focus on supporting schemes to develop ICVs and ensure that they don’t become blind to problems in custody? This is an area for more exploration and research.

Recommending change

Independent custody visiting takes place under the UKNPM and Louise, the NPM Coordinator, was keen to ensure the new Code was ship-shape for our international duties. One area that gripped the group was considering how schemes make recommendations for change. This is an important part of UKNPM duties and takes place at a local level. We considered whether the annual reports that schemes produce could focus on their recommendations and responses from constabularies. ICVA could, potentially, complement this with an annual ICVA report of our national themes and recommendations, with the NPCC responding. We would need to consider how to apply this to governance in Scotland and Northern Ireland, too, who have different systems in place. This would make much better use of the work that is already taking place and is a great idea.

Making the best use of data

Unsurprisingly, our stakeholders see real value in the findings of ICVs and wanted to ensure appropriate processes are in place to share information. The IPCC has force liaison officers who could share lessons learned from other areas. This would help ICV schemes to prevent harm across all forces. ICV feedback will also provide a timely account of what is happening on the ground. This could be used to promote good practice or instigate reviews to APP or advice from the College of Policing.

In short, there is a great deal of potential to use the information that our ICVs report in a more meaningful way with our partner organisations. Any new Code will need to recognise that and structure reporting from schemes in a way that can be applied to wider strategic work on custody.

Voluntary attendance

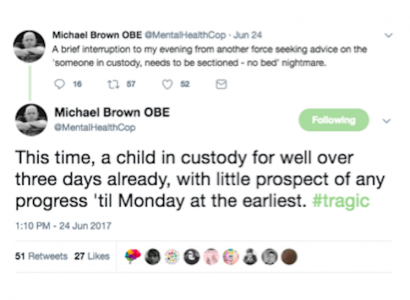

I am very aware that many vulnerable detainees are being diverted away from custody, sometimes through using voluntary attendance. Voluntary attendance requires a person to meet with the police as a designated time and place. It is viewed as a more proportionate way to interview people. This has many advantages, including keeping vulnerable people and children away from custody. However, I remain concerned about the lack of safeguards on this process and am working with partner agencies on this project. Upon discussion, we felt that it was simply too early to put voluntary attendance into the Code. We do not yet know enough about it or how best to respond. This is an area to watch.

Joining the dots

I am finishing this blog as I am shadowing an inspection into police custody. I am so grateful to the inspectorates for having me along; it’s incredibly useful. The inspectorates are our partners in the UKNPM and we pursue the same goals. We want safe custody that treats people respectfully and humanely. ICVs are in and out of custody frequently and speak to those held in detention. The inspectorates take a much deeper dive into practice, conditions, process and vulnerability every few years. We bring different strengths and I am sure that, together, we could make a greater impact than we do alone. I am pondering this. I need to think about how I can share this learning with Scotland, Northern Ireland and other schemes. I need to think about how we can do this without causing considerable workloads or encroaching on our roles, but it’s something that I need to think through, thrash out and discuss with colleagues. It is not beyond our wit, I have been so impressed by the inspectorates and I am keen to join these dots – whether that’s through the Code or other mechanisms.

What do you think?

This is just the start of a period of consultation and reflection, coming from just one angle. I haven’t even discussed what a good scheme looks like – how to value and train our volunteers, how often we should visit, what should ICVs look out for and record? There are so many questions. Some of these will be answered in a new Code; others will be answered elsewhere. Right now, I am keen to hear from you. If you are a member organisation, if you are an ICV, if you work in custody, if you are a member of the public – this is your scheme and your service. Comment to tell us what you think matters and why and we will include your views in the mix. I will carry on musing.