At the end of a recent blog, ICVAs CEO wrote most eloquently (I’m not creeping to the boss honest!) on detainee dignity and rights. This is a point that we often discuss and one of the most compelling and often heard narratives as to why we should uphold the rights and dignity of those held in police custody is often ‘they haven’t been found guilty of anything’.

I have a problem with this narrative. Whilst it can be effective in terms of winning over some, often harder to reach, audiences to discuss the importance of detainee dignity and rights, as my CEO wrote, we don’t care or indeed know if someone is found guilty or not. We don’t judge on offences for which someone has been arrested and indeed should never know. It really doesn’t make a difference to us or the ICVs.

I have a long history of working either directly in or with crossover to the Criminal Justice Sector and it’s a sector I am passionate about working in. I don’t think I have ever once thought that a certain group of detainees in any form of custody deserved any different treatment to any other. Those in police custody do not deserve to be treated with dignity any more than those in a prison, in a mental health setting, or an immigration detention centre who may have been found guilty of the full range of offences, and some not having an offending history at all.

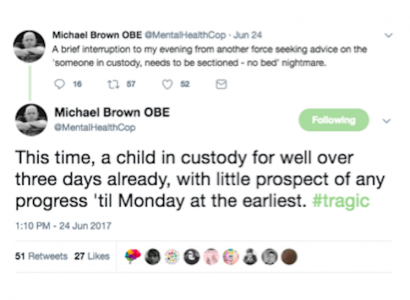

Once the state deprives someone of their liberty, regardless of the reason or circumstance, it has a responsibility for that person. The person relies on the state for many if not all of their basic needs. The state can protect against vulnerability or it can increase it. Guilt or lack thereof is not, and should not, be a factor in determining treatment of those detained, be that for a short period in police custody, or a lengthy prison sentence or section.

It is difficult to maintain your dignity when eating from a microwave tray with a spork or a cardboard spoon. It’s difficult to maintain your dignity when using a toilet which is pixelated in part but does not cover your whole body (I understand why this is so, but the point remains). It’s difficult to maintain your dignity when you might need to ask people for toilet paper (I think that risk assessed detainees should never have to do this and yet they do on occasion).

If you were in the position of the state in terms of endeavouring to maintain detainee dignity with these challenges implicit in the system (and they are examples from police custody rather than other detention types), would you be prepared to withhold them for someone you thought was guilty of an offence, or had been arrested for an offence which you personally find unpalatable? Would you withhold eating utensils? Would you honestly deny someone toilet paper? I suspect not. And that is because regardless of guilt, the idea of withholding basic human needs to anyone does not sit comfortably with most of us.

Over the past few weeks my twitter feed has had a lot of tweets/articles/pictures etc surrounding the protect the protector campaign. This may appear to deviate from the topic of the blog but again, I think we all, as direct or indirect agents of the state need to change the narrative in terms of how we talk about detainees sometimes. Most notably there have been many accounts of officers being assaulted by detainees in a variety of ways, without doubt causing injury and trauma. I categorically do not support any assault on the police. I want to be very very clear on that point.

However, I have seen tweets and articles using some extremely strong language for those who have committed the offences, animals, vermin, detritus. I don’t think people should ever be referred to in this way. I don’t think it is an acceptable type of language for someone in a position of power and social responsibility to use and so I would like to offer an alternative, a change to the narrative.

Why don’t we separate the person from the behaviour – I accept someone can behave in a vile manner but that does not make them a vile person surely? Someone can be capable of disgusting behaviour without anyone needing to call them a generically disgusting person? It seems like pernickety semantics I know but think about it for a minute. Separating the behaviour from the person allows us to express our emotions surrounding someone’s actions, but without writing that person off completely. It allows us to vent, and show support for colleagues, but without the underlying pejorative tone or indeed dehumanisation of the whole person.

If we can change the narrative, if we can hold detainee dignity in high regard irrespective of guilt, if we can talk about behaviours rather people, this surely will have an impact on how people treat and think of those deprived of their liberty.

What we say about those detained, particularly those thoughts we air in public, undoubtedly has an impact on the wider view of society to those in detention. If you are, or ever have been part of the state, or work in this arena, isn’t that as much of a responsibility as any other part of detainee welfare?